I was born in Liberec,

Czech Republic

Born in 1986, I grew up in the tumultuous 1990s.

Then businesses grew, money flew, and the nation was slowly getting used to freedom and democracy after 50 years of Communism.

But the story of Barbora, the writing enterpreneur, starts more than 30 years later.

I wrote my first novel when I was 10. And realized that I wanted to be a writer.

Then came a crash against the wall of reality around me:

“You can’t make a living from writing—unless you’re a journalist, and you’re not thick-skinned enough for that.”

Unfortunately, that was true in 2006. Nothing at the time suggested that in the online world, every brand and every store would soon need—and pay handsomely for—someone who could write.

So, I decided to study a “respectable” and “secure” profession at the Faculty of Education.

History was always meant to be a hobby, a detour that couldn’t pay the bills. So, I enrolled in the teaching program, pairing obligatory English (“languages will always earn you money”) with history.

In 2006, I sat in my first history seminar, and the teacher addressed us: “You, historians.”

Really? I’m a historian? I can be a historian? Wait—historians write and make a living from writing. Count me in.

In 2013, I began a PhD program while teaching English at a primary school. I published several academic papers, taught at university, and spoke at conferences. The texts I published—with a few exceptions—were unreadable. The writer in me was hiding in a corner, pretending she didn’t exist. Academic correctness, insecurity, and fear of reviewers’ criticism tied my hands. Scientifically, it was fine, but creativity was missing.

When I went on maternity leave in 2016, I enjoyed being my own boss. I answered to no one except a tiny creature whose sleep schedule I had to respect. But alongside that, I could study, write academic texts, travel to conferences, and teach part-time at the university. It was paradise because I didn’t have to worry about making a living.

But even then, shadows crept into my paradise. Aside from the suspicion that academia wouldn’t pay well—full-time offers weren’t exactly raining down—I realized I wasn’t even good at it. I lacked the patience for archival digging, and my academic writing was dull. Most of all, I dreaded dedicating my life to a single era and years to one narrow topic. I enjoyed history as a whole. More than that—I relished other subjects too.

In 2020, I held my PhD diploma in hand—and was horrified to realize my imagination hadn’t glimpsed past this moment. Three years of maternity leave had flown by, and I had only three more to figure out how to make a living after that.

When borders closed, my borders disappeared

Then COVID hit. It turned the world upside down and brought a boom in online education. Everything and everyone went online, and I discovered how many possibilities the digital world offered.

First, I launched a mom blog, then a history blog. I did this moprimarilyor joy, not for money—after all, who pays for history, right? I taught privately, slowly reviving the writer hiding in the corner because, suddenly, one could make a living by writing. I wrote articles and websites, studied persuasion psychology, marketing, and algorithms, and searched for my place in this new world of possibilities.

Today, the only boundaries are the ones you set for yourself—even national ones. If you know a foreign language, you can write for readers and clients worldwide. Stationed in Prague, I started writing in English, and one door after another opened. I wrote for clients in India, the US, Denmark. I contributed to Canadian and Australian magazines. I write about alpine skiing for an American website—and even have a newsletter subscriber from Mongolia.

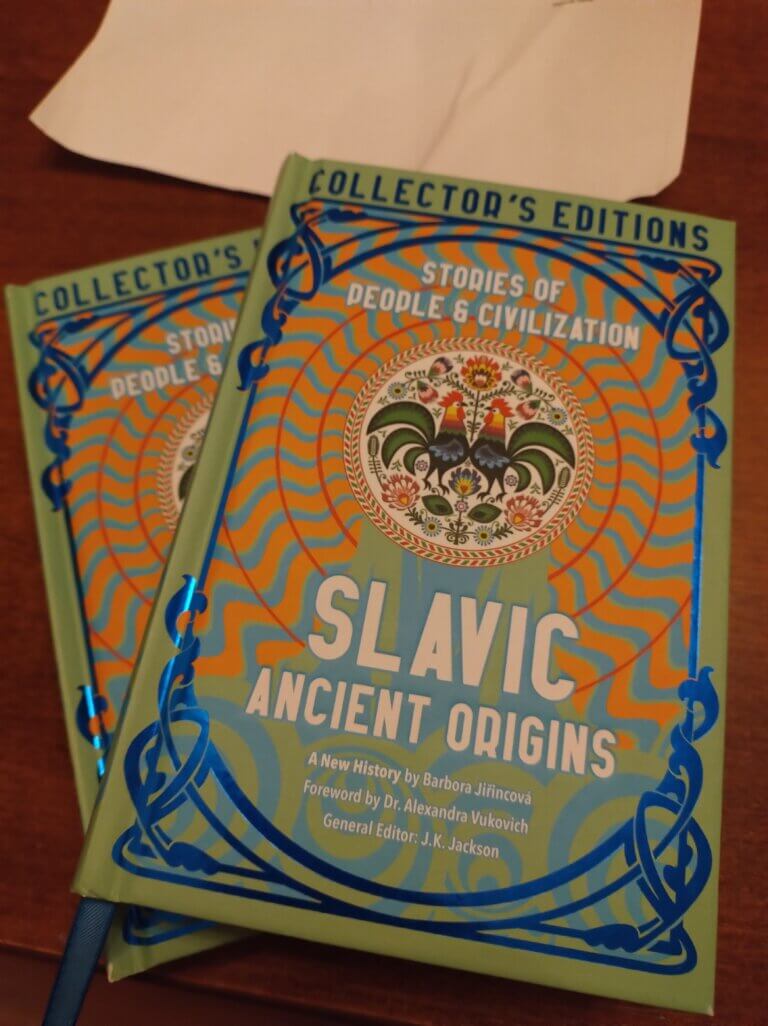

In 2023, I received my first historical book deal with a British publisher. I refused to believe the amount in the contract—until the first payment hit my account. So this is what a writer can earn today? Why didn’t anyone tell me when I was fifteen?

Sure, books weren’t my primary source of income. Marketing and sports journalism brought in more. But when I held my first published book before Christmas 2024, I knew—this is it. This is what I want, but it’s just not like this.

I couldn’t sell or promote my book properly—I’d given up all rights in the contract. I couldn’t even offer it to Czech readers—I’d signed away translation rights. I disliked the cover and marketing—I felt it deserved better than the sales it got, and I couldn’t do anything about it.

So, I started learning what authors earn in 2025. Not just copywriters or article writers but book authors. I found horror stories about publishers squeezing writers for just 5–10% of profits. About lifetime work being thrown among other titles and left to collect dust. Many companies profit by “granting dreams” of publication to naive authors, taking only 50% of all sales. However, I also discovered platforms like Amazon, Kobo, and Barnes & Noble Press have opened up direct publishing. Where writing books is real business.

If you want to succeed as a writer, you can’t just write. You have to be a writing entrepreneur. A book is a product that can bring cash 70 years after your death. The writer has the idea, the work, and the vision—without us, publishers and bookstores have nothing. Most authors don’t realize this and still live in a world where “you can’t make a living from writing” and are grateful when someone “makes their dream come true.”

So I walk this way. I publish directly, retain my rights, and handle my own marketing. I want direct contact with readers and to give them what they want without delay. Based on feedback, I aim to improve my books with every re-edition.

I fully understand that books alone won’t feed a family. Because people don’t only read books—they also listen to podcasts, watch videos, play games, and buy gifts. One book idea can be monetized over again—that’s how you do it when you’re a writing entrepreneur.

I still write for clients—it keeps burnout at bay and gives me money to reinvest.

I wrote my first novel at age 10. It took me 25 years to get here. But it was worth the journey.

Only after I published my first Czech book did I dare face another huge issue: my hatred of social media. For three years, I tried to build a business and somehow follow the modern rule: “If you’re not on socials, you don’t exist.”

I tried them all—Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Threads, Pinterest, LinkedIn—and they drained me. Success never came because my heart wasn’t in it.

I see social media as one of the greatest threats of our time. They harm our youth, drain our brightest minds with silly reels, divide society, and ruin civilized debate.

I won’t join the chaos, post, or build a follower base—even if it means earning less. I’d rather pay with cash for book, podcast, or article ads than pay with my time and soul for organic reach. And anyone who closes Instagram because of my ad and opens my book? It’s worth every penny.

I write books and write stories. I tell historical stories in podcasts and lectures. I create what I’d want to read, play, or wear—but couldn’t find anywhere.

I don’t just write about history today. I write in the self-help niche and romantic fiction. I do marketing writing, using my empathy and understanding of human psychology to help good brands sell more. I write about alpine skiing, tell athletes’ stories, and write sales copy for ski brands.

Because that’s why I left academia—to let myself be carried by inspiration wherever it takes me. To ask curious questions, offer surprising answers, and look at the world with childlike wonder.

My

Values

Human

We live online, sell online, write online. But there’s always a person on the other side of that line. Whatever I do, I will not forget the human.

Storytelling

Your story is the best tool if you want to sell. A story sells itself.

Empathy

Sales psychology has enormous power and empathy for the reader and customer even more so. But empathy is also about knowing the thin line between persuasion and manipulation.

Efficiency

Not every text has to win a Pulitzer or garner applause from the professional community. The text should fulfill its purpose.

Who

I have worked with